The Disconnect Between the Cost of Education and How it’s Rewarded

The last three decades have seen a diminished return on investment (ROI) for college graduates as growth in the cost of higher education has outpaced inflation while mean earnings have stagnated.

In our previous post we presented an annotated history of student loans. This post examines the evolution of the return on investment (ROI) for college graduates over time and presents recommendations for how we can adjust how education is sold for the better.

The last three decades have seen a diminished return on investment (ROI) for college graduates as growth in the cost of higher education has outpaced inflation while mean earnings have stagnated. As a result, in many fields of study it has become harder to earn a degree and realize a reasonable return. Below we examine this disconnect in greater detail.

Cost of Higher Education

Growth in higher education costs has outpaced inflation by an average of 3.7 percent since 1989. The average cost of tuition and fees has more than doubled across all sectors of higher education. A 1996 report from the United States General Accounting Office (GOA) to Congress found a 234 percent increase in 4-year public colleges and institutions from 1980 to 1995. The majority of increases were attributed to the expansion of services with rising costs driven by increases in faculty and an increased dependency on tuition as the primary source of revenue.

To ensure rising tuition costs have the least impact on enrollment, institutions have an incentive to provide readily accessible funding to their students. As a result, the size and importance of financial aid departments within institutions has grown. Among 4-year public postsecondary institutions, the reliance on tuition and fees has increased from approximately 18 percent in 1999 to almost 21 percent in 2018. Among private for-profit institutions, this proportion of total revenue has increased from approximately 86 to 95 percent over the same period.

The revenue from tuition collected in the first two years of an undergraduate program has better margins than that collected in years three and four. The price per credit hour remains relatively stable throughout the degree, but the cost of service increases as more qualified instruction is required in later years. As a result, institutions have the double incentives to (1) capture as many first year enrollments as possible to increase revenue and (2) have high attrition rates for the 3rd year onwards to reduce costs. Both of which are at odds with the goal of providing an education.

University dropout rates serve as a reminder that not every student debt holder has access to post-graduation employment opportunities via a diploma. Approximately one in every three students dropout before earning their degree, with 38 percent of non completers associating financial pressure as a reason for not continuing. Of those students that stay the course, only 23 percent finish within the first 4 years on average.

How Society Rewards Education

When individuals are educated, their ability to contribute to society and prosper increases. The United States considers a high school diploma as the foundation of this education hence the taxpayer funded subsidies for education for K through 12. The justification is simple: if society is receiving the benefits of an individual educated to this point, they should cover the costs of it. Conversely, it’s argued the benefits of higher education are mostly held by the individual, who is thus responsible for its cost. While the average Bachelor’s degree recipients see about 80 percent more in mean earnings than those with only a high school diploma, the total return of higher education to the individual has been significantly diminished due to (1) compensation for graduates growing at a much slower rate than the cost of education and (2) a lack of repayment support for borrowers.

Compensation Growth < Cost of Education Growth

As previously reported, tuition and fees grew by over 200 percent from 1980 to 1995. Over the same period, median income rose only 82 percent and the Consumer Price Index rose 74 percent; leaving an aggregate growth rate of eight percent in purchasing power. This mismatch has worsened over the last three decades, with mean earnings among Bachelor’s degree recipients growing a measly 0.61 percent above inflation on average since 1989. Overall, it’s estimated the 10-year return on investment (ROI) of a Bachelor’s degree has seen a seven percent compound annual rate of decline since 1996 considering:

- Opportunity cost of attending college, estimated as the average mean earnings of a high school graduate compared to a Bachelor’s recipient

- Average student debt per Bachelor’s recipient (combined Federal and private)

- Average grants and work study received over four years per Bachelor’s recipient

- Average out of pocket expense over four years to cover education costs after considering loans, grants, and work study

- The cost of loan payments over a 10 year amortization period, which is considered standard for federal loans.

Inadequate Repayment Support

Income aside, the way student loan borrowers are supported is another reflection of how society rewards higher education. Since debt has become a pillar of how higher education is accessed, the support system provided for both the onboarding and repayment of debt burdens is a critical part of the success of borrowers. Those that rely on student debt to fund their education (58 percent of all Bachelor’s recipients) have six months to find a proper source of income before leaving the grace period and entering repayment. At which point, any outstanding interest accumulated is capitalized and added to the original principal for Federal loans. Practices like interest capitalization have drastic impacts on the total payback amount and time over the lifetime of the loan. Partnered with antiquated payments processing and awful user experiences among repayment services, borrowers face an uphill battle to do what they know is right. As of the second quarter of 2019, almost 12 percent of the current federal loan portfolio was in default. Student loans go into default after over 90 days of delinquency.

Yes, the mean wages for college graduates significantly exceed the earnings of high school graduates. Yes, there is still a lot of work to be done before the federal programs live up to their intent to lower financial barriers to education.

Impacts of The Disconnect

The consequences of the imbalance between the cost of education and how it’s rewarded are evident considering the reduced spending and delays in financial milestones, reduced saving, diminished retirement planning, and higher rates of job hopping among student debt holders.

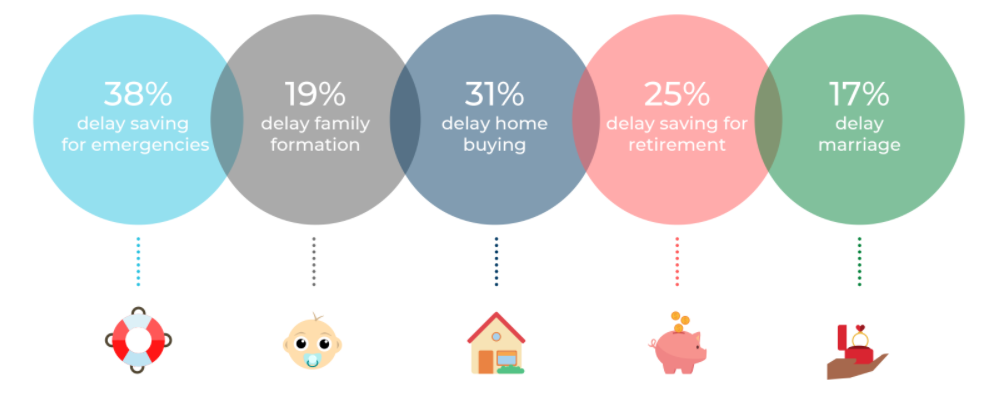

With limited discretionary income and high monthly student loan payments, borrowers have pressure to reduce spending. This has caused many debt holders to delay major life events like marriage, home buying, and family formation. One in ten borrowers report they are unable to buy a car and 31 percent of millennials have delayed home buying as a result of student debt.

In addition to reduced and delayed spending, individuals are delaying emergency and retirement savings. On average, 38 percent of employees report having less than $1,000 and impacts to retirement contributions are being seen across multiple age groups. 25 percent of Millennials report they have delayed 401(k) contributions as a result of student loans and increased borrowing and co-signing among parents and other guardians has resulted in approximately $289 billion of outstanding student debt being held by individuals age 50 and older. With rates of retirement savings already low among American households, the estimated retirement savings deficit is estimated to be upwards of $4.13 billion.

The socioeconomic impacts of the disconnect between the cost of education and how it’s rewarded impacts the lifeblood of the economy, those small and medium businesses, the most. The detriment of financial stress on employee engagement and productivity is well documented. Four out of five employers identify their employees’ financial stress as a major factor in job performance. Productivity among the workforce is largely dependent on employee wellbeing, of which financial health is a major contributor. Only 13 percent of U.S. workers say they have a great job and only 63 percent report being actively engaged. Financial stress continues to play a major role in employee engagement:

- Absenteeism/Tardiness: employees with high levels of debt are twice as likely to miss work than those with low debt and 34 percent of employers note increases in absenteeism and tardiness as a result of financial stress.

- Ability to focus: 35 percent report being distracted at work due to personal financial issues.

- Turnover: the rate of voluntary turnover has reached a high since April 2001 reaching 2.4 percent in 2018.

As a result, employees searching for ways to break the disconnect between education costs and its rewards resort to job hopping and finding additional sources of cash to supplement their income.

Lowering Financial Barriers To Education

Lowering the financial barriers to education requires a rebalancing of the cost and reward of higher education with adjustments to each layer of the system. These are our recommendations:

- Share the burden

- Service better

- Lend less

We focus on changes driving immediate impact for the person burdened by student debt. Certainly, the way we price and deliver higher education requires long term efforts. We have to begin by reducing the burden on the debt holder.

We'll dive deeper into these recommendations in our next post on lowering financial barriers to education.

Want to share your thoughts? Email us: hello at getdolr dot com